Once again, I find myself reflecting over another great stay in Santa Cruz. It was my fourth time in Guatemala, and I've now spent over twelve months of time volunteering at the clinic! By this point it truly feels like a second home. Whenever I have more than a few weeks off, I find I now take it for granted that I'll return.

At only two months, this was the shortest period time I've been able to stay for a while (the downside of being back in school). Fortunately, by this point I benefit from ever-increasing groundwork, connections, and momentum from previous visits. Although it felt far too short, it is still incredibly encouraging to hit the ground running each time I return. Thanks to help from so many friends, supporters, classmates, and the support of those who live in Santa Cruz, the trip proved among the most successful and productive to date!

I was able to start the trip off on the right foot thanks to the wealth of incredibly donations that were bestowed on the clinic. In February, I received a 400lbs shipping pallet of top-notch diagnostic equipment and medications from an organization called Heart to Heart. I’d been able to check all the supplies off of a list that I thought would vitally serve the clinic, and they only charge the cost of shipping. I received several additional boxes full of supplies from Gifford Medical Center, my hometown hospital. For most of last spring, a quarter of my little apartment bedroom was stacked floor-to-ceiling with boxes ranging from Vitamins to procedure lights.

All told, I’d assembled a total of ten 50 pound suitcases filled with donated medical gear. At first, I was absolutely flummoxed as to how I’d get them across the border, especially without a truck to drive this time. Shipping the supplies might have cost thousands in fees and taxes, and it probably would have been lost in transit anyway. Fortunately, I had two friends from medical school that decided to join me as volunteers at the clinic this summer. The little brother of a third friend from Dartmouth also happened to be traveling through Guatemala this summer, along with four of his classmates. With everyone taking one or two suitcases as checked luggage, we successfully muled tens of thousands of dollars worth of new materials to Guatemala for just a handful of extra baggage fees.

Unfortunately, once we showed up in Santa Cruz, it looked like these supplies would push the clinic’s storage problem to the breaking point. All but one of the clinic bathrooms had been converted to ad-hoc storage spaces. You could barely open some of the doors due to without triggering a landslide of cardboard boxes, trash and inaccessible yet essential supplies. The l stacks of suitcases and boxes in the pharmacy had become home to a bustling metropolis of cockroaches and spiders.

My friends and I ended up devoting nearly the entire first week to a massive cleaning, exterminating, sorting, and organizing effort. At some point we determined that we had no choice other than to construct new shelving in several closets if we wanted materials to be accessible. My carpentry skills are limited to say the least, but we were fortunate to have the engineering genius of my friend Chad Cosby in mix. After he’d drawn up a blueprint, we got to work (often by headlight, as several had no functioning lights). It took another few days and multiple trips across the lake to the hardware store, but I’d say the final result is sturdy enough to hold up for years to come and has perhaps doubled the clinic’s storage capacity.

With the working space cleared out, we were able to focus on one of this trip’s major goals—to get the clinic’s laboratory up and running. We’ve had several extremely competent volunteers in the past that had brought some supplies and implemented testing protocols. However, the efforts would usually cease once they left the clinic. Our goal became to not only significantly expand the scope of our testing, but make the use of the lab a regular fixture in clinic life.

I have no a background in microbiology. However, I was fortunate enough to be joined for the summer by my friend Adam Ackerman, who spent many years working in a pathology lab before medical school. Adam started by reaching out to his former colleagues and soon had acquired a donated centrifuge from Fletcher Allen and high-end refurbished light microscope from Mass General. He introduced me to faculty in the pathology department at FAHC, letting me arrange several afternoon tutorials. In that way, I was able to learn protocols for many simple techniques, such as gram staining, preparing wet points, centrifuging blood and feces, and making peripheral blood smears.

After setting up the microscope and centrifuge and assessing the available materials, it was clear we were short a lot of critical elements. There wasn’t much other choice than one of the always-avoided errand trips to Guatemala City. After purchasing another $500 of supplies and reagents in Guatemala City, we had everything we needed for a simple but functional laboratory.

It soon proved that creating a physical laboratory was the easy part. Becoming proficient in the protocols ourselves was the first hurdle. Adam and I taught the clinic’s medical assistants phlebotomy, and had numerous vacutainers of own blood drawn to practiced preparing, staining, and reading smears. I’d collect fecal samples of anyone with diarrhea for closer examination. As my comfort increased, I worked to integrate the lab testing into everyday life at the clinic.

I am quite proud of what we were able to accomplish in the end. The clinic now uses a hematocrit centrifuge to screen for anemia in all prenatal check-ups. The staff can quickly prepare peripheral blood smears, helping to differentiate between various subtypes of anemia. It may also prove a powerful diagnostic tool for intracellular parasites such as malaria. Our providers run rapid antigen assays on patients in for H pylori, rotavirus and adenovirus. Stool samples can also be prepped as ova and parasite exams under the microscope. Skin scrapings can help diagnose scabies and fungal infections. The clinic now has occult blood tests and urinalysis in its arsenal as well. In the past, the clinic lost valuable funds paying for necessary laboratory tests to be run by private labs in nearby cities, often an hour away. The clinic is now both saving money and providing better care to patients thanks to the new in-house diagnostic capabilities. Most excitingly, having a laboratory has sparked a curiosity among the clinic staff, most of whom are indigenous Mayans. It’s been so gratifying and exciting to show our nurse practitioner white blood cells under the microscope, or help one of the assistants perfect her venous blood draw.

Of course, one of the big objectives for the summer was to complete the truck ambulance. On that front, there were both breakthroughs and hold-ups. As it stood, I had to leave before being able to witness the final results. However, the parts are all in motion. Barring further roadblocks, the truck should be in place and functional later this month.

As it happened, last spring, I decided to take advantage of an offer extended by the government university in the department capital of Sololá. The Universidad del Valle runs a technical training program in automobile body repair. Although it appeared primarily superficial, they truck had considerable body damage from an unknown past accident.

I accepted the university’s offer and had the truck delivered. The technical program offered to completely refurbish the truck’s exterior as a training project for its students. They are only charging for materials, and at a steep discount. After talking about it for years, the truck is being completely repainted white, with “Ambulancia” and the names of the three communities stenciled on the side. I’ve always believed that clearly distinguishing the ambulance is vital to deter non-medical abuses of the truck by the drivers or community officials.

The technical program is bestowing many additional practical improvements as well. The partition between the cab and the truck bed is being removed to allow for free communication between the driver and the patient. The height of the camper that covers the back is being raised to allow the medics space to work and sit.

Unfortunately, as you might guess, the refurbishing process has lasted far longer than I expected. The labor is all provided by students, and there proved to be many unforeseen repairs along the way (it turned out parts of the chassis were badly warped and needed to be reworked). As a result, the truck was in the garage for the entire summer. The last time I visited, all the seats and non-metal components were still completely disassembled, and they were hammering out the body. However, I’ve been assured that the truck is less than a month from completion.

Another hurdle which I had to take on this summer involved transferring ownership of the truck from me to the collective ownership of the three villages. It’s a prerequisite step in order to receive Guatemalan license plates and registration. Unfortunately, it’s been the most ghastly round of red tape I’ve seen to date. To file the paperwork, I had to relinquish possession of my passport to the Guatemalan tax agency for an undisclosed period of time (I’d been told around a month). For that reason I’d been unable to complete the transaction the year before. As a result, the truck had been forced into inaction over the past year since it wasn’t technically legal to drive yet.

With limited time this summer I knew I had to act fast. I found a business that specialized in greasing the wheels with taxes and paperwork. Reluctantly, I handed over my passport and a good stack of cash. For the next month, I remained undocumented. Delay and complication stacked up one after another. The entire time I was sweating bullets as significant parts of my paperwork were forgeries I had to have made at the Guatemalan/Mexican border last spring when paying truck import taxes. In the end, I had to force the agency to do a document “hostage exchange” with only a week to spare before my departure. They took possession of our Guatemalan pediatrician’s driver’s license, as well as the documents for Don Andres, the village elder who’s the spokesperson for accepting the ambulance. As of now, the paperwork is still stuck in the pipeline somewhere. Most recently, I’ve been informed I need to pay another fine “for taking so long to complete the paperwork”. All in all, it makes tax time in the US seem like a breeze. Anyway, I am pressing hard (from abroad, with emails and skype calls) to wrap this up. It will be such a relief to complete the long, very expensive chain of bureaucratic maneuvering I’ve undertook since bringing the truck in a year before.

In any case, if all goes to plan, the truck will be in the communities where it belongs within the next month. I am already planning a return trip for several weeks in February. A top priority will be to formally present the vehicle to the towns and convene the community educational forums I intended to this summer. However, it should be transporting those in need long before that.

To be continued...

A lab retrospective: The extremely congested laboratory space (and generally bufoonery) we had to contend with last year.

A lab retrospective: The extremely congested laboratory space (and generally bufoonery) we had to contend with last year. The kitchen midway through its cleanup and transformation... I wish I'd thought take a photo when it was still a total kitchen

The kitchen midway through its cleanup and transformation... I wish I'd thought take a photo when it was still a total kitchen The new lab features more bench space than you can shake a purple-top tube at!

The new lab features more bench space than you can shake a purple-top tube at! The beautiful desk we found as a throne for the beautiful scope.

The beautiful desk we found as a throne for the beautiful scope.

If you can get excited about working with poo, you will be an amazing lab tech!

If you can get excited about working with poo, you will be an amazing lab tech!

Since there was no way to change or purchase tires in Santa Cruz, I had to remove them two at a time, carry them by boat to Pana, and have the new tires mounted on the metal hubs. Tires are heavy.

Since there was no way to change or purchase tires in Santa Cruz, I had to remove them two at a time, carry them by boat to Pana, and have the new tires mounted on the metal hubs. Tires are heavy. It turns out there were limited jobs I was qualified to do... namely cleaning...

It turns out there were limited jobs I was qualified to do... namely cleaning... While the girls of course got to man the power equipment.

While the girls of course got to man the power equipment.

I was finally allowed to handle power tools!

I was finally allowed to handle power tools! Flash forward a few days! The benches are nearly complete, and we're working on the tracks and wheels for the removable backboard.

Flash forward a few days! The benches are nearly complete, and we're working on the tracks and wheels for the removable backboard. I consider the stickers to be the true moment of transformation

I consider the stickers to be the true moment of transformation These two little pieces of metal cost about $1000 and took dozens of hours of direct time and over a year of waiting to get.

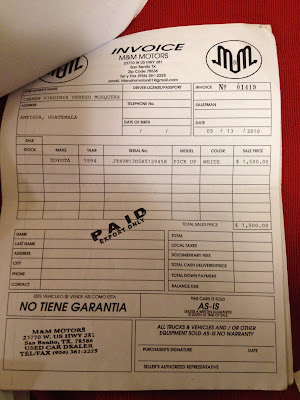

These two little pieces of metal cost about $1000 and took dozens of hours of direct time and over a year of waiting to get. Here is all the paperwork that we ended up needing to present to the Guatemalan government to get the truck imported, pay all taxes, get a title and license plates, and transfer ownership. Most of them are generally stamped, embossed, signed, or highlighted.

Here is all the paperwork that we ended up needing to present to the Guatemalan government to get the truck imported, pay all taxes, get a title and license plates, and transfer ownership. Most of them are generally stamped, embossed, signed, or highlighted.  My favorite two documents--my forged bills of sale! They are actually quite superb quality... but I was still afraid I'd be detained at any given time for the months these were being scrutinized by the Guatemalan vehicle tax folks.

My favorite two documents--my forged bills of sale! They are actually quite superb quality... but I was still afraid I'd be detained at any given time for the months these were being scrutinized by the Guatemalan vehicle tax folks.

Unfortunately, this is the best photo we seem to have taken of the finished interior of the ambulance. This is prior to the mounting of the oxygen tank in the interior, which lies horizontally behind the driver and passenger seats.

Unfortunately, this is the best photo we seem to have taken of the finished interior of the ambulance. This is prior to the mounting of the oxygen tank in the interior, which lies horizontally behind the driver and passenger seats. Setting up the switchbacks to ascend 3000ft from Santa Cruz to Solola.

Setting up the switchbacks to ascend 3000ft from Santa Cruz to Solola. Although the ride was bumpy, it was encouraging to learn the backboard was the most comfortable seat in the ride.

Although the ride was bumpy, it was encouraging to learn the backboard was the most comfortable seat in the ride. Vrooom!

Vrooom! Noe put superhuman efforts into making the ambulance a reality, especially while I was out of the country. Its completion is now more his accomplishment than anyone's. Here we are, finally arrived in Chuitzanchaj.

Noe put superhuman efforts into making the ambulance a reality, especially while I was out of the country. Its completion is now more his accomplishment than anyone's. Here we are, finally arrived in Chuitzanchaj. At long last, the ambulancia has arrived in the hill communities that it will serve!

At long last, the ambulancia has arrived in the hill communities that it will serve! The cocodes (village elders) start lining up in preparation for the formal presentation of the truck

The cocodes (village elders) start lining up in preparation for the formal presentation of the truck